Having just finished our recent online film festival (19-28 March 2021), we are pleased to take this opportunity to share some of the thinking that went into making our first online and largest ever edition. In many ways the organisational and curatorial decisions that we made along the way were informed by the unavoidable and highly uncertain situation of the COVID pandemic and the global movements for racial justice that rocked 2020.

Curation

The first curatorial step was settling on the conference theme of “Creative Engagement with Crisis” which was decided in March 2020 before anyone knew how big COVID would become. It was fortuitously ready-made to capture the 2020 moment.

We asked those working in the fields of visual anthropology, ethnographic film and adjacent disciplines to reflect on the notion of crises and the creative engagements they engender. How are visual anthropologists and the communities that we have been working with responding to the crises of our times? How might research work in film and related media help us to move beyond the disruption and despair to renew and rethink visual and sensory anthropology? What is the place of creativity, resilience, agency and hope in these responses?

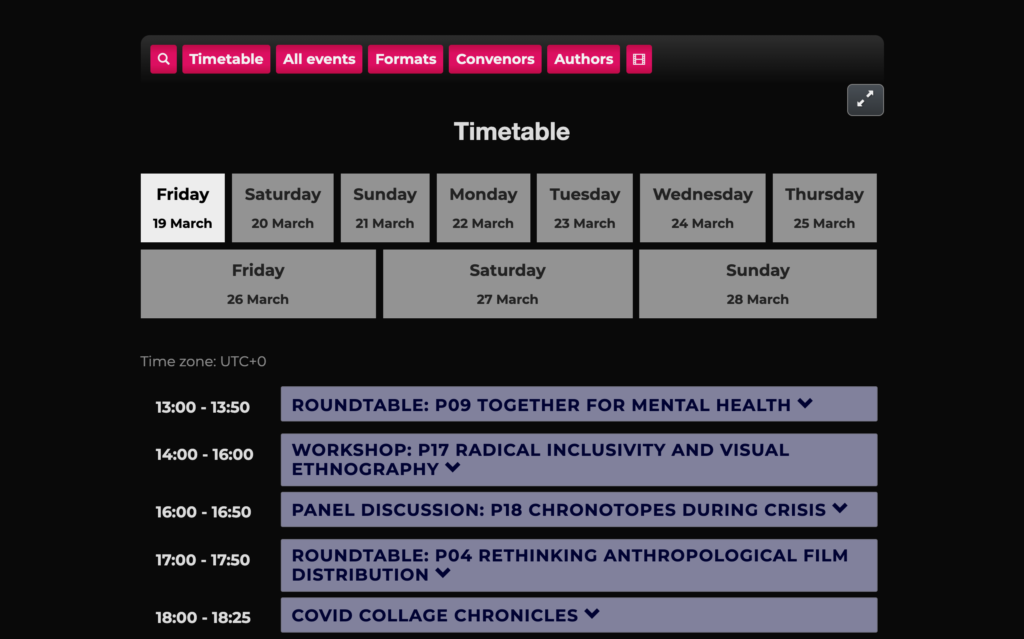

We had such a fantastic response for panel proposals, we wound up with 43 panel sessions in total. This was almost twice the size of the conference portion at the previous RAI Film Festival in 2019 and forced us to rethink how best to showcase such a rich and varied intellectual contribution from so many scholars.

In order to help provide a focal point amongst all the panels, we decided early on to add two keynote addresses and invite two prominent scholars in visual anthropology, Faye Ginsburg (NYU) and Stephanie Spray (USC). In her talk Ginsburg drew on her long-standing work with First Nations/Inuit media makers in Canada and Australia and considered how Indigenous media makers are developing their own archival imaginaries in ways that are often counter to dominant archival practices. Spray centered her talk on the often overlooked ethical and creative work of “maintenance”, proposing that visual and sensory anthropology should reposition itself to make maintenance central to its concerns. Spray drew her own film work, in particular on her body of work developed in Nepal (of which Manakàmana is her most famous piece) and on her work-in-progress in Patagonia, looking at the creation of a conservation and rewilding park.

The keynotes resonated strongly with themes that emerged from the conference in ways that helped to shape the overall programme once our film selection process began in the autumn of 2020. As we worked through a most impressive range of films submitted to the festival from 78 different countries, a number of key themes started to emerge: a strong engagement with archival practices; a marked interest in exploring the ways anthropology and visual anthropology in particular can rethink collaborative and co-authorial modalities; a clear focus on filmmaking and scholarship emerging from marginalised communities, and a related interest in thinking through anti-racism and decolonisation. Many of these themes were also explored by conference participants in their panels, and came to shape the festival ‘organically’.

As curators we also brought our own agenda to play in making some key decisions to shape the overall festival. We were troubled by the death of George Floyd and wanted to respond constructively as protests swept across the globe. We felt that it was important for us to feature racial justice and anti-racism as prominent themes in the festival. In the end this resulted in a number of interventions that percolated through the programme as a whole.

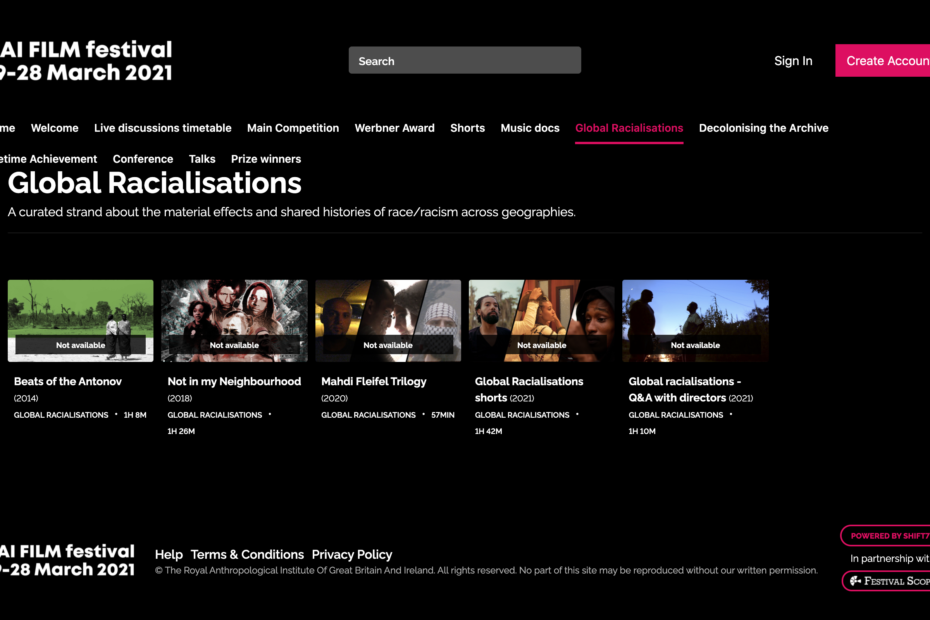

Yasmin Fedda and Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan guest curated a strand addressing processes of racialisation in different contexts, “exploring the material effects and shared histories of race/racism across geographies”, as they state in their curatorial note. We were also pleased that Elena Guzman and Miasarah Lai of the EthnoCine Collective joined us to run an Anti-racist Filmmaking Workshop which included a live feedback session with three selected filmmakers. The live session gave the filmmakers the rare chance to discuss aspects of their work as it engaged with questions of representation, racial justice and anti-racism. Alongside these initiatives we curated a film strand, Decolonising the Archive, from our festival film submissions to feature a strong selection that addressed the politics of historical media collections and how they are mobilised in the present.

We also continued and reinforced the RAI Film Festival’s long standing commitment to Indigenous filmmaking, which it honoured in a number of ways; the Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk was awarded the RAI President’s Award for his film One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019), and Tote_Grandfather by Tsotsil director Maria Sojob, shorts by Dinah Sam (Cree), Uapukun Mestokosho (Innu) and the Miyarrka Media (Yolngu) featured in the competitive sections of the film programme. In addition, a “live-streamed only” event celebrated the Indigenous Directors from NYU’s Culture & Media Program Teresa Montoya (Diné) , Angelo Baca (Diné/Hopi), Teresa Martinez-Chavez (Zapotec), Ikaika Ramones (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), in a format that honoured the filmmakers’ vision about how the works should be distribution and displayed. During the live Q&A, Teresa Montoya spoke about a politics of refusal (referencing Audra Simpson) underpinning the filmmakers wish to be in control of how the films circulate and are seen.

And following from our 2019 film festival where we introduced a short film prize, this time we decided to give even more prominence to short form filmmaking by selecting more than double their number in the 2021 edition. As the online world gives platforms and opportunities to showcase more shorts than ever before we have seen the form expand and gain popularity with audiences and makers alike. We had therefore no trouble curating ten themes short film collections, addressing issues such as the environment, migration and sexuality, to name but a few.

Concerns about the content were of course not the only ones we had.

Organisation

When we started out planning for the festival at the beginning of 2020, we fully expected to return to the Watershed Cinema in Bristol, England in what would have been our fourth consecutive festival at the venue and follow the pattern of our previous festival in combining films and an academic conference. When the call for conference panels and the film submissions opened we still assumed we would be clear of COVID by the time of the festival in March 2021.

But as the summer wore on and the second wave of infections was taking its heavy toll, we were forced to call off all plans for a face to face in person festival and embrace a fully online format. By this time, we were not alone in making this decision. Many other film festivals had already had to make this move, so we had a good chance to study how others were managing the transition. One of our first points of reference was Distribute 2020, run by the Society for Visual Anthropology and the Society for Cultural Anthropology who had put together their own thoughtful and inspirational “Play Book” on how to run an online film festival/conference. At what for us was a crucial early stage, both Jerome Crowder and Harjant Gill generously met with us to talk us through the lessons that they had learned.

After a couple months of search and debate, we decided in November 2020 to hire a commercial online film festival platform run by Festival Scope. We felt that this would be our

best option to prioritise an online HD film streaming experience, offer an intuitive user interface and provide an all-in-one solution for selling passes and tickets. However, this online cinema platform was not a solution for all of the festival events. Festival Scope did not offer any in-built livestream capabilities that could accommodate live discussions around the films and the associated academic conference.

We decided at this stage that Zoom would be the best solution for the live discussions. We figured that most participants would be familiar with it by now, so no training would be required. The ‘meeting’ format, with the right safety protocols in place, seemed to provide a good balance between accessibility, ease of participation and a sense of ‘being together’. For sure it is not perfect, but it was the best we could find at the time.

With Festival Scope and Zoom as the two big platform decisions in place, we still had a lot to figure out. None of us had ever organised an online festival, so we knew that we would have to learn as we went along. It was also clear that the move to the online format was forcing us to rethink every part of our festival step by step and would take us to places that we could not fully anticipated at the start. Along the way we tried to embrace the new possibilities that our online format makes possible. This meant some important new changes in our format.

- We decided early on that we would incorporate as much pre-recorded material as possible in order to make it more accessible to a wider audience- 24/7 over 10 days, rather than our

usual 4 day festival with tightly scheduled and overlapping events. - From this principle it logically followed that we would ask of our conference participants to

record their presentations in advance. This was a big ask for our presenters, who did a

fantastic job on the recording of their presentations with creativity and innovation. The panel

recordings were important to free up time, so that we could devote all live-streamed time for

discussion. - The online format also opened the chance for nearly every one of our filmmakers to be able

to join us for Q&A sessions. This is always something that we have always hoped to make

happen at our Film Festivals but had faced significant obstacles of travel costs and time

constraint. - And maybe most important of all, the online format has allowed us to reach beyond our face-to-face festival audiences in ways that we have only been able to imagine up to now. We have done our best to expand our accessibility and draw together a wider, more diverse and varied audience than ever before.

There are of course many limitations – however flexible, the online format is just not as conducive to creating connections and informal conversation as a live in-person event is. There is an immersiveness to in-person events that just doesn’t translate to the online festival model. And we were all too aware that there is a very real digital divide that meant streaming videos is not accessible to large parts of the world. Also there are major problems in catering equally for all time-zones with live-streamed discussions. Despite the limits, we hope that through both the curatorial and technical decision we made as organisers and the contributions from our collaborators, academic partners and conference presenters, we succeeded in offering a festival that speaks to the present moment and to the concerns of the discipline of anthropology, the documentary filmmaking world and beyond.

We still need more time to fully digest what worked best and what can be improved upon from this still so recently finished festival. We will, over the next month, continue to assess the feedback and reflect with our partners as we put together a more comprehensive festival report and recommendations. But we can be sure that part of our next challenge will be to think about how to create a blended online and in-person festival that delivers the best of both.