In 1923 Dziga Vertov was flattered to be labelled a ‘shoe-maker’ rather than an ‘Artist of Soviet Cinema’. He knew that documentary film-makers “must be more aware that the boot is made of leather than of the wax that is used to shine it”. It is precisely this pre-occupation with substance rather than surface that characterizes our concern with documentary. So in the spirit of Dziga Vertov: shoemakers of the world unite!

Crittenden et al., 1986, p. 4

In the early morning of St Andrew’s day 2021 I learned that a giant of cinema, and through, among other things, his notion of observational cinema a key figure in the development of ethnographic film, had passed away a few days previously, in his home, surrounded by his family. Colin Young was also an alumnus of the University of St Andrews, and a true Scot, although he since his graduation had lived in the Scottish ‘diaspora’ in places such as California and England. There is no chance that this brief tribute to the man will do him justice, and really express the enormous importance he had in shaping so many minds about cinema in general and documentary in particular, not to mention ethnographic film and visual anthropology. This homage is written on behalf of the Nordic Anthropological Film Association (NAFA) and yours sincerely personally.

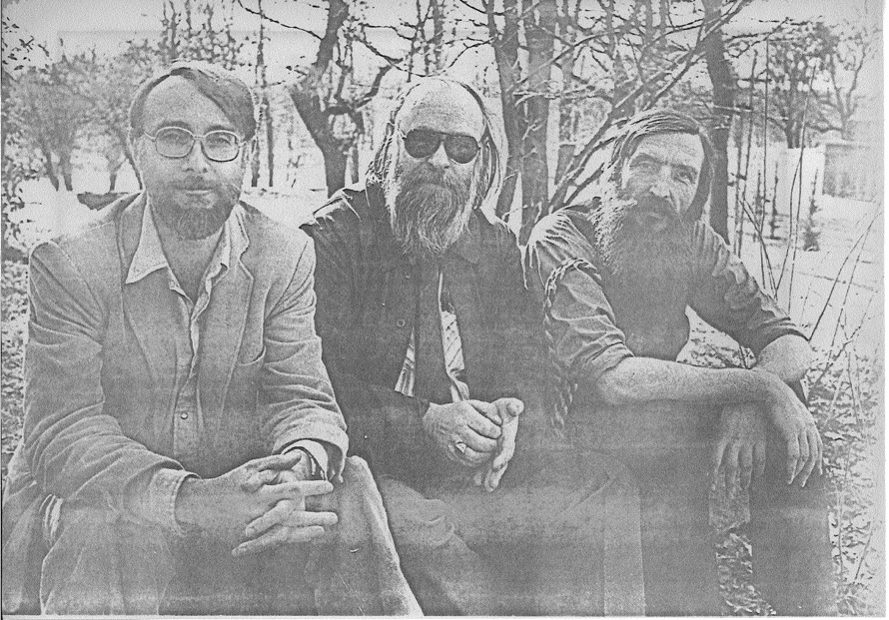

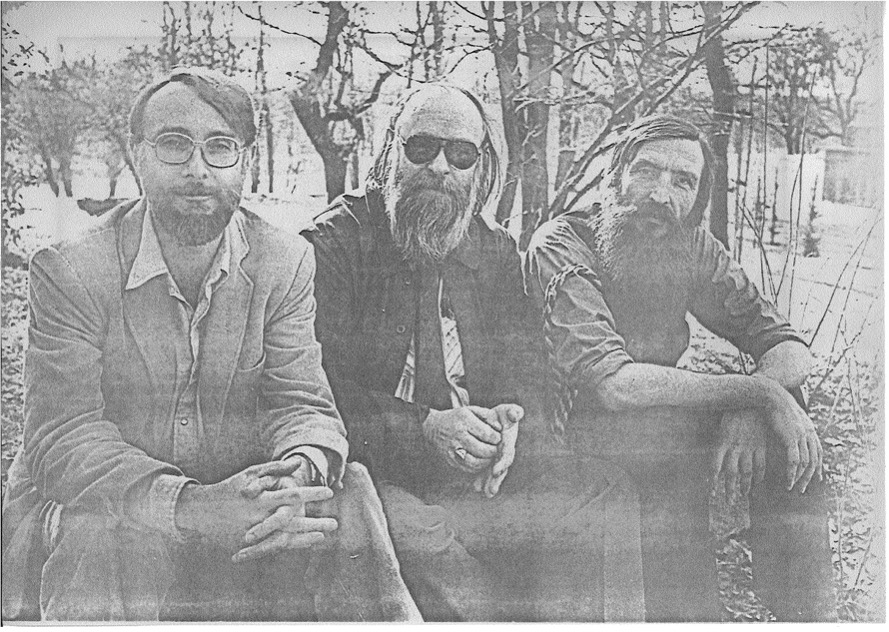

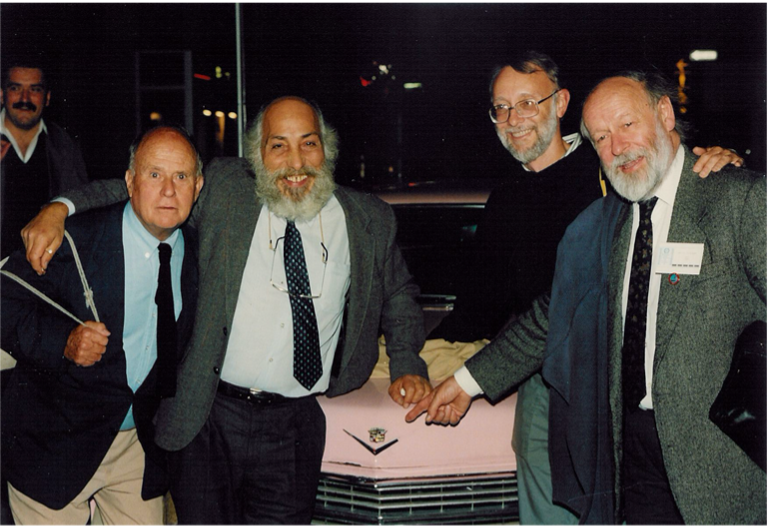

Colin became the first honorary member of NAFA and was instrumental in the formative first fifteen years of the association’s existence, remaining a close NAFA ‘family member’ ever since (see also Crawford, 2017). I believe the first time I met Colin in a NAFA context was at our very first international festival of ethnographic film in 1979, making the NAFA festival the oldest specifically ethnographic film festival in Europe, which was held at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. Colin was still the relatively newly appointed first director of the National Film and Television School (NFTS) in Beaconsfield in the UK. He introduced a kind of cooperation that lasted for several years by bringing with him a filmmaker or filmmakers who had something interesting to say about documentary film. I thus believe he for example introduced David MacDougall, who had been part of the courses in ethnographic film that Colin had run at the UCLA, to NAFA, and vice versa. In 1979 he came to Stockholm with Peter Watkins, the maker of the infamous docudrama The War Game from 1966, which was produced for the BBC but was so controversial in a British political context that it was not actually aired on the BBC until the mid-1980s. I seem to also remember that it was through Colin that a relationship was established between NAFA and Gary Kildea, who briefly studied at the NFTS. Both David MacDougall and Gary Kildea are honorary members of NAFA.

Colin Young thus attended several of the early NAFA festivals, always presenting films that showed his acute sense of how film could be of use in and to anthropology. He introduced Herb di Goia, head of the documentary programme at NFTS, to NAFA, and together they created what became a tradition, that they would bring students from the NFTS, particularly those with film projects that evidently were of anthropological interest. In those early years these included Graham Johnston, with his film Muktuk – Whale Meat for the Winter (1983), from the Canadian Arctic, Mark Bryce’s film The Sacred Harp Singers (1983), from Texas, and later Molly Dineen’s Home from the Hill (1987), about a retired soldier returning to the UK from Kenya. Another important role played by Colin Young in those days was that he told us in NAFA about films that could be interesting to have in our ethnographic film archive, and which we would therefore show at the festivals. These included films from the Anglophone world of documentary by for example David and Judith MacDougall, Robert Gardener, John Marshall, Ian Dunlop, Gary Kildea, Bob Connolly and Robin Anderson, Timothy Asch, Asen Balikci, Richard Leacock and Jorge Preloran but also from the ethnographic films made in the Francophone world by key figures such as Jean Rouch, Edgar Morin, and Luc de Heusch, the French connection, as it were, also linking up NAFA with the anthropologists and filmmakers Colette Piault and Nadine Wanono, as well as the Atelier Varan film school. He also made sure that we in NAFA were familiar with the emerging ‘new’ observational styles of more mainstream documentary, such as the works of Nick Broomfield and Joan Churchill, later Kim Longinotto, all three trained at the NFTS. Basically, Colin Young instilled in NAFA a sense of what ethnographic and documentary films could be, in a very undogmatic and open-minded manner. It was through Colin Young, probably more than anyone else, that NAFA started to build up its extensive network that bridged the gap between anthropology as an academic discipline and the world of cinema.

Colin’s direct involvement with the early NAFA festivals culminated in 1986, where he had a share in the plans that resulted in the 7th NAFA festival being held at the Danish National Film School in Copenhagen in 1986, the director of which was Henning Camre, who in 1992 succeeded Colin as director of the NFTS. Colin was too busy to bring students to NAFA, and after he retired from the NFTS he became busy with the Ateliers du Cinéma Européen, training European film producers. By then, however, his impact on NAFA and ethnographic film in the Nordic countries was already firmly established and there is no doubt that he in a more indirect sense also influenced later developments of visual anthropology, such as the master programmes first in Tromsø in northern Norway and later at Aarhus University in Denmark. His seminal article on ‘Observational Cinema’ (Young, 1995 [1975]) had by then already turned the observational approach and films – representing, as it in many ways did, ethnographic fieldwork – into what Marcus Banks (1992, p. 124) described as ‘the jewels in the crown of the ethnographic film canon.’ This, however, led to what I would describe as two rather widespread myths. Firstly, that the observational approach could be reduced to a detached way of filming, indicated by the often-misunderstood term ‘fly-on-the-wall’ and that it is based on a third person passive voice, meaning basically that there is no or a very limited relationship between the filmmaker and the subjects of the film. Secondly, that it denotes a very rigid concept of filmmaking governed by a series of very inflexible rules. I would claim that Colin Young’s ideas, quite the contrary, were based on a fundamentally humanistic and anthropologically inspired idea that the relationship between the subjects and the filmmaker is the most important of all, akin to Rouch’s idea of shared anthropology. A third myth that has perhaps grown out of these two, is that we in teaching ethnographic filmmaking consider the observational style the only way of making ethnographic films. While some teachers may subscribe to such a notion, I can assure the reader, and not least our students, that one thing I learned from Colin is that we must all find our own styles when making a film.

Colin’s hiatus in attending the NAFA festivals did not mean that his influence on visual anthropology in the Nordic countries ceased. One other key role was the way in which he encouraged the publishing of books on ethnographic film-making. One of his former teachers of documentary at the NFTS, Toni de Bromhead, herself a professionally trained anthropologist, has thus published no less than three books with Intervention Press (1996; 2014; 2019) and would probably never have embarked on such a project if she had not had the full support of Colin Young as a first reader, helping launch the books, for example at the Royal Anthropological Institute in 2015, as well as writing a concise foreword to the first book, in which he once again emphasises the role of the people of an observational film: ‘The New Wave directors were still in control of their actors; the new documentary film-makers gave up that control in favour of the “autonomy” of the people they were filming.’ (Young, 1996, p. xi). Again thoughts that resonate with the spirit of anthropological enquiry.

In NAFA we had the great joy of being able to welcome Colin Young back to our festivals at a late stage in his life, even though his mobility had become rather restricted. In 2009, for example, he made it to our 29th festival held together with the University of Primorska in Koper in Slovenia, clearly demonstrating that whatever ailments he had, had not affected his notorious ability to sum up a film in a few sentences that were always constructive even when they might be critical. His final attendance in a NAFA festival was two years later, bringing him back to his alma mater at the University of St Andrews in 2011 for the 31st NAFA festival. Adrian Strong, one of the filmmakers present, and I took turns in pushing him around the university and town in his wheelchair, followed by a group of almost star-struck visual anthropology students from northern Norway, another generation of ethnographic filmmakers enjoying Colin’s thoughts, charisma and personality. He did, of course, not go to bed assisted by his allocated helper, Adrian, until he had enjoyed a wee dram in the company of the growing entourage, all, of course, invited to Colin’s hotel room. We are going to miss him so much at NAFA but rest assured that his spirit will roam our festivals, as has been the case of other deceased key figures, such as Heimo Lappalainen, who was most definitely a soulmate of Colin, and the one who as our general secretary originally brought him into the NAFA fold.

Peter I. Crawford

General Secretary of NAFA

Professor of Visual Anthropology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway Tromsø, 30 November 2021

References

Banks, M. (1992), ‘Which films are the ethnographic films?’, In: Crawford, P. I. and D. Turton (eds.), Film as ethnography, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 116-130.

Bromhead, T. de (2019), Muddied Waters. The Fictionalisation of Ethnographic Film, Aarhus: Intervention Press.

Bromhead, T. de (2014), A Film-Maker’s Odyssey. Adventures in Film and Anthropology, Aarhus: Intervention Press.

Bromhead, T. de (1996), Looking Two Ways. Documentary Film’s Relationship with Reality and Cinema, Højbjerg: Intervention Press.

Crawford, P. I. (2017), ‘The Nordic Eye Revisited. NAFA, 1975 to 2015’, In: Vallejo, A. and Peirano, M. P. (eds.), Film Festivals and Anthropology, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 179-191.

Crittenden, R. and C. Potter, with Herb di Goia, Barrie Vince and Colin Young (eds.)(1986), ‘Editorial’, In: Confronting Reality: Some Perspectives on Documentary, CILECT Review. The International Journal for Film and Television Schools, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 3-4.

Henley, P. (2018), ‘The Authoring of Observational Cinema: Conversations with Colin Young’, In: Visual Anthropology, 31, pp. 193-235.

Young, C. (1996), ‘Foreword’, In: Looking Two Ways. Documentary Film’s Relationship with Reality and Cinema, Højbjerg: Intervention Press, pp. ix-xii.

Young, C. (Young, 1995 [1975]), ‘Observational Cinema’, In: Hockings, P. (ed.), Principles of Visual Anthropology, Second Edition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 99-113.